Community-Based Mapping

Cartographic representations

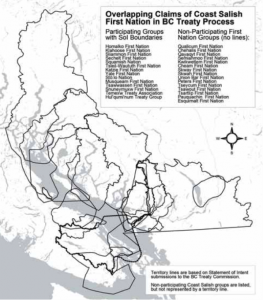

While historically, maps have been used by nation-states primarily to assert their territorial rights and reinforce their power over indigenous and other communities, there are now multiple examples in which indigenous groups in different parts of the world have embraced mapping as a way of reclaiming their sovereignty over the lands, negotiating aboriginal rights, and regaining dignity during conflicts with governments and institutions. This work of using cartographic representations and methodologies to defend and reclaim territories has become part of a counter-mapping movement. The challenge, moving forward, is to grapple with the practical problem of implementing socially and politically powerful initiatives that acknowledge and embrace the critique that such representational practices reduce and essentialize elegantly relational indigenous ontologies.

Contemporary indigenous mapping projects of this theme’s research members involve developing approaches and tools to effectively visualize and communicate indigenous peoples’ knowledge and experience of land for inter-generational knowledge transfer, public education, indigenous rights assertions, and in land and resource consultations. CICADA members are developing tools in a variety of geographic regions and disciplines, and the cross-disciplinary interaction among academic and indigenous partners will lead to new avenues being pursued. Integrating new mapping and remote sensing techniques into indigenous mapping projects and the development and use of derived products and analyses are other opportunities that we would like to further explore.

The mapping dilemma

Although these techniques and practices present a range of opportunities for indigenous communities, members of this research theme are cautious of the transformations of indigenous perspectives on place, which these high-tech visual maps require. The work risks losing the aural structure of indigenous knowledge to become visual. Traditional knowledge can become dehumanized to be coded in computing language. As such, digital mapping technologies risk reinforcing the subordination of indigenous spatial world-views to western technologies and perspectives through those different transformations.

“If my theory of being, of becoming, and of belonging is distanced, then I’m an empty vessel. I’m not a human being.” -Alais Ole-Morindat

On the other hand, there are several instances in which certain indigenous groups are taking advantage of geospatial technologies to push forward their political agendas. In what might be viewed as progress over previous participatory mapping practices, many of these projects explore the possibilities of combining indigenous and scientific spatial knowledge to develop hybridized forms of spatial representation that recognize and respect the uniqueness and importance of indigenous spatial expressions.

Mapping can be either empowering or a tool of control, depending on which side of the map you are; depending if you are the mapper or the mapped. This was one issue that was discussed at length at the 2015 CICADA conference. Collaborator Kevin Gould introduced a well-known quote by activist Audre Lorde: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” In relation to this, Gould contended that maps are weapons and questioned whether these weapons are in fact the master’s tools that perhaps reinforce colonial relations or allow those relations to continue. In response, indigenous partner Alais Ole-Morindat emphasized the importance of having indigenous people at the centre of mapping projects, explaining that failing to do so risks dehumanizing indigenous people: “If the technology is yours and ideas are mine, I am lost because I am dehumanized. I am left behind. […] If my theory of being, of becoming, and of belonging is distanced, then I’m an empty vessel. I’m not a human being. […] And this is how I find myself not only marginalized and cut into pieces, but dehumanized”. Gitxaala anthropologist and CICADA collaborator Charles Menzies concluded that what is at issue is not the tool itself, but rather how mapping as a tool is deployed and appropriated.

These hybrid cartographic forms of expression employed by CICADA indigenous partners do not reverse colonial social relations, but rather, as mentioned Coast Salish partner Kathleen Johnnie at the 2015 conference, rework and reconfigure them, helping to develop a new space of mutual understanding, provided that the balance between western science and indigenous knowledge is respected. The transformation of indigenous knowledge and spatial expressions into cartographic artifacts remains a complex issue. One of the challenges that will be faced by these communities will be to make sure that these mapping applications can really serve their needs and be adapted to the uniqueness of their spatial knowledge instead of forcing them to adapt this knowledge to the tools available. We must work in close collaboration with communities to develop practical, affordable, and theoretically informed methodologies for conducing, analyzing and cartographically representing indigenous perspectives on land tenure, territory, use and occupancy, and significant sites and landscapes.

Research questions

The questions with which the researchers in this theme are concerned are the following:

- How can communities and partners involved in CICADA work together to make sure that participatory, collaborative and counter-mapping activities and tools are designed to fit the needs of the communities (present and future)?

- What can we learn from previous mapping experiences from partners and communities involved in CICADA?

- Is there a common framework for cartographically representing indigenous peoples’ life projects on a continental or global scale that doesn’t risk problematically reducing those visions into finite categories that undermine rather than celebrate indigenous territories, governance and rights?

Theme Leaders: Sébastien Caquard, Nicole Fenton, Brian Thom

Theme Contributors

Benoit Éthier

Murray Humphries

Jochen Jaeger

Colin H. Scott

Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert