Indigenous Development Alternatives: Social Justice, Resource Rights, Institutional Hybridity

Indigenous Development: Social Justice, Resource Rights, Institutional Hybridity is a research project that focuses on the intersections between social justice, resource rights and institutional hybridity on land to which indigenous peoples have rights and/or exclusive title in Australia. We reconceptualize notions of development, recognizing variation and hybridity and shifts away from the hegemonic western constellation of discourses to examine local institutions and the hybrid western/customary forms that they must take where indigenous political geography and identity remain dominant.

Project leader Jon Altman delivers the lecture, ‘Genocide and Intervention in contemporary indigenous Australia: Raphael Lemkin Down Under’, at the Dept. of Anthropology, McGill University, Oct. 16, 2017. A brief text version appears in Arena Magazine June/July 2017 (no 148)

This project takes place in north Australia, from Kakadu National Park to the west to the lands of the Yolngu to the east. Most of this area was gazetted the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve by the colonial state and then was converted without a land claims process to Aboriginal ownership (inalienable freehold title) under land rights law from 1976. The indigenous population of the region is about 18,000. This area of 120,000 sq kms is covered by tropical savannah, escarpment and high biodiversity flood plain. Four Indigenous Protected Areas, Warddeken, Djelk, Dhimurru and Yirralka, were declared in Arnhem land for world class environmental values. Additionally, Kakadu National Park has World Heritage listing for its cultural and environmental values.

Indigenous people in this region experience deep poverty. There are two major operating mines at Jabiru, within Kakadu National Park and at Gove (both owned today by RioTinto) that provide employment opportunity, though the Bininj in the west and Yolngu in the east are reluctant to take up this employment. Mining agreement payments have totaled tens of millions of dollars since the 1970s.

This is a region of Australia where the state looms large, not in terms of governance because communities are sparsely populated and very dispersed, but in terms of transfer payments to deliver a limited range of citizenship entitlements to communities and considerable welfare to individuals and families. High dependence, poverty and a degree of political disengagement makes the regional population highly susceptible both to state policies and unilateral changes in state policies.

In recent years, but especially since the 2007 Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) Intervention by the Commonwealth, there has been an emerging neoliberal consensus that indigenous people in this region need to adopt western norms and join the mainstream so as to close statistical gaps between them and other Australians. In the postcolonial period, livelihoods were a hybrid composed of state subsidy, some engagement with market capitalism, and activity in a non-market customary sector. Such hybrid livelihoods were underwritten by the state and especially a productive community-controlled ‘work for the dole’ program called the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) scheme and robust resource organisations. The provision of environmental services in Indigenous Protected Areas in this region with funding support for rangers under the Commonwealth Working on Country program has provided some ‘mainstream’ employment opportunity outside the mining and public sector. This prompts issues addressed in the area of Livelihoods and Food Sovereignty, as existing forms of postcolonial livelihood have eroded.

There are also real threats to regional biodiversity from climate change, feral animals, and exotic weeds that alongside a decline in on-country living is making people more dependent on store-bought rather than hunted bush or country foods.

Indigenous Development: Social Justice, Resource Rights, Institutional Hybridity’s key questions that link with other CICADA research themes include the following three questions:

- How is it that neoliberal ideology can trump evidence that in this remote region economic hybridity rather than imagined market capitalism delivers more productive livelihoods?

- How can the challenges to regional biodiversity be ameliorated so that forms of food security based on production for domestic use can be revived?

- What are local notions of the good life and how do people view the policy unilateralism that has eroded both the limited autonomy and ways of work organisation that have allowed a meshing of indigenous priorities with productive forms of external engagement with capitalism and the state?

The key question that indigenous people in this region grapple with is how they can be empowered to actually influence the form that their livelihoods will take in the face of state domination and an enduring ideological commitment to late capitalism.

Additionally, these communities are considering how their comparative advantage in natural and cultural resource management can be fully realised so as to ameliorate inevitable negative impacts on their ancestral lands and resources that precolonially and even recently have delivered a degree of ‘food security’.

Conceptual and Methodological Connections within CICADA

There are many cross-cutting links between this research and Life Projects, Customary Tenure, and Conservation and Protected Areas.

Starting with the land base, the region this research project is interested in is almost all of aboriginal statutory title that is also recognised in subsequent inferior native title law. Of particular significance is the current existence of a statutory land council, the Northern Land Council, with legal obligations to ensure that the free prior and informed consent of traditional owners is secured before any commercial development by a third party occurs on their land. FPIC provisions in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act give traditional owners de facto mineral rights (as exploration can be vetoed) and rights over all resources for customary use and along the coastline a potential to combine customary rights with commercial rights.

A combination of statutory and customary rights have been mobilised to allow the declaration of significant Indigenous Protected Areas over about 40 per cent of this region, while nearly 20 per cent is declared national park. The declaration process has required large numbers of traditional owner groups to allow the joining of their lands into environmental commons that are being managed by community-based ranger groups. For many, such work involving protecting ancestral lands from external threatening processes (wild fire, feral animals especially cats, pigs and buffalo, exotic weeds, and marine pollution) is a life project that accords well with living well, making a livelihood, and living on country.

This project aims to explore the governmental, institutional, and endogenous barriers to such a vision of the world that is often encompassed in aboriginal discourse and ideology if not in practice.

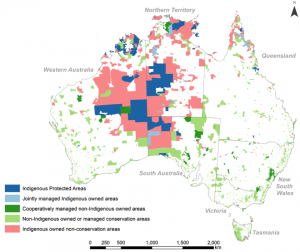

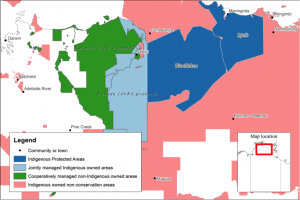

A tenure map of Australia shows the region of interest in the north of the Northern Territory, with a following large scale map depicting just Kakadu and west Arnhem (See Map 1 &2). Indigenous Development: Social Justice, Resource Rights, Institutional Hybridity and its indigenous partners are using this statistical picturing as a means of advocating for the conservation possibilities of indigenous communities’ relatively intact ancestral lands.

READ MORE:

Karrkad Kanjdji Trust. 2018 Annual Report: “New Futures on Ancient Country.”

Jon Altman’s February 2018 submission for reforms to the Australian Native Title Act 1993

Project leader: Jon Altman

Associated Research Themes: Customary Tenure; Livelihoods & Food Sovereignty; Conservation & Protected Areas

Visit The Institute of Postcolonial Studies website to learn about related activities.