Inuit

Baffin Island, Nunavut

Academic co-investigator Thierry Rodon has been working with Inuit communities to research northern governance, indigenous policies, sustainable development, joint management of natural resources, indigenous education, and participatory democracy.

Academic co-investigator Thierry Rodon has been working with Inuit communities to research northern governance, indigenous policies, sustainable development, joint management of natural resources, indigenous education, and participatory democracy.

“On first consideration, Inuit may appear to have vaulted from life in isolated small societies characterized by little knowledge of the outside world and scant capacity to cope with the complexities and demands of an increasingly global consciousness in a dangerous and complex world. We acknowledge that there is some truth in this observation, but…it also contains important misconceptions and a serious underestimation of the strengths inherent in the original Inuit societies. On the evidence of what they have achieved in the last two generations, it is clear that the original societies of Inuit had developed a number of attitudes and practices that have been capable of successful adaptation to new challenges. That all of what Inuit have achieved to date, in the arena of internal diplomacy and externally as well, has been achieved peacefully and without disadvantage to other people or groups, should recommend their approach to others.“

-Inuit Diplomacy in the Global Era

[ezcol_1half id=””class=”” style=””]

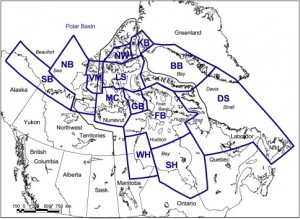

James Ford, CICADA co-investigator, has been examining the effects of climate change and climate policy on Inuit communities in Canada. Ford has established the Climate Change Adaptation Research Group based in the department of geography at McGill University. The group’s research examines the ways in climate change vulnerability, adaptation research and planning amongst Indigenous populations all intersect with science and policy. Ford is interested in new methods for studying and tracking adaptation at global and regional levels. Ford’s research also examines the effects of climates change on Inuit communities’ food security and considers the gendered aspects of climate change on female food security. Ford is also interested in the impacts of climate change on Inuit demographics, with an interest towards fertility and migration.[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end]

“We identify policy priorities that can be implemented within existing policy frameworks today and outline boarder principles of adaptation applicable in multiple contexts. Importantly…Inuit are not powerless in the face of a rapidly changing climate. Adaptation options are available, feasible, and Inuit have considerable adaptive capacity as history and current experience shows. With support from territorial and federal levels and local action to identify risks and plan for adaptation, some of more severe manifestations of climate change can be moderated.”

-Climate Change Policy Responses for Canada’s Inuit Population: The Importance of and Opportunities for Adaptation.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

Mario Blaser, CICADA collaborator, has developed Understanding the Past to Build the Future, a five-year multidisciplinary study of the history of the Inuit Métis of southern Labrador. The research aims to investigate the Inuit occupation of Southern Labrador by collecting and analyzing evidence of Inuit-European interactions and documenting cultural changes. Research is conducted through archaeology, ethnography, archival study, and genealogy.

George Wenzel, CICADA collaborator, has been partnering with the Inuit of Clyde River, Nunavut, to examine wildlife management, hunting, food security, and subsistence practices. Wenzel’s research has focused on the significance of polar bears to Inuit communities’ subsistence hunting practices, and has also examined the impacts of climate change on Inuit subsistence.

“The crucial adaptive problem is not the fate of polar bears or seals, nor which species may fill the newly vacated niches, but rather how the global environmental political regime will respond to Inuit ecological choices. What the Inuit must make clear is that their “subsistence adaptation” is not only about how to maintain the hunting component of the system, but also, and perhaps more importantly, how to sustain the social economy of ningiqtuq when well-meant decisions in Washington, London, Geneva and Brussels about polar bears, narwhals and caribou are ignorant of their cultural impact. All this is to say that the environment to which the Inuit must adapt is a far more complex one than the one experienced by their Thule forebears.”

Gabriela Gamez of IsumaTV and Katie Sinclair from McGill University were present at CICADA’s 2016 Meeting to talk about the IsumaTV project, which in Sinclair’s words is an “Inuit film, TV, and digital media organization based in Nunavut”. Among other services, the organization provides a collaborative platform for indigenous filmmakers and other multi-media creators. IsumaTV is open to indigenous creators from around the world, thus promoting inter-community communication.

Gabriela Gamez of IsumaTV and Katie Sinclair from McGill University were present at CICADA’s 2016 Meeting to talk about the IsumaTV project, which in Sinclair’s words is an “Inuit film, TV, and digital media organization based in Nunavut”. Among other services, the organization provides a collaborative platform for indigenous filmmakers and other multi-media creators. IsumaTV is open to indigenous creators from around the world, thus promoting inter-community communication.

Due to Canada’s stark inequality between provinces in terms of access to internet services, IsumaTV provides an infrastructure network which allows to access the website’s media content at high speed to low-speed communities. Access to media is also greatly facilitated through the Indigenous Film Network (IFN), which installs high-definition projectors in selected communities. The advantages of improving internet access in these communities is the potential to strengthen language and culture through new media, improving education and job training, create jobs and encourage community-led economic development.

Better internet access also means an improved local capacity to monitor government action and the exploitation of natural resources. As such, IsumaTV became involved in the promotion of indigenous rights in the context of mining activity, when the Mary River iron ore project was initiated by Baffinland in the vicinity of Igloolik, where IsumaTV is based. About 2000 people live in Igloolik, most of which speak Inuktituk. Although a process of community consultation took place in order to begin mining activity, Sinclair notes:

The way IsumaTV contributes to the discussion around indigenous rights and mining is that the platform allows community participation in forms other than inaccessible written documents with legal and scientific terminology, which governments tend to use to address concerned populations, as Gamez notes.

Associated Projects

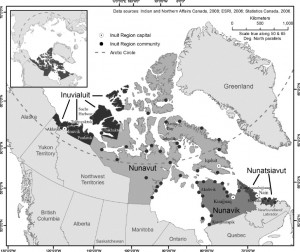

Environmental Impact Assessment and Social Impact of Mining in Eeyou Istchee, Nunavik, and Nunavut