St’át’imc

Interior of British Columbia

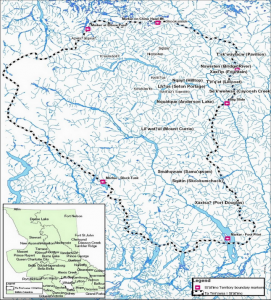

The St’át’imc are an Interior Salish Nation whose territory is located in the southern Coast Mountains and Fraser Canyon region, in the interior of British Columbia. There are 11 St’át’imc communities. The St’át’imc vision of the good life is of a continuing and renewed relationship between the St’át’imc people (úcwalmicw – the people of the land) and the land (tmicw).

The good ways of life (Nt’ákmen) include: traditional forms of governance; speaking the language and passing it on to young people; positive family relationships and expansive webs of helping and sharing; passing on names; and training for different roles and inherent gifts, such as dreaming, sensing, knowing, feeling, and the ability to do things in a good way. As was discussed at the 2015 CICADA conference, the key element in Nt’ákmen is that the St’át’imc be able to live off the land and actively engage in hunting, fishing, and harvesting. The way things are (Wa7 tu ts’illa7 I tsa) is expressed in the following statement pronounced by Elders:

In 1911, St’át’imc Chiefs, with the help of anthropologist James Teit, drafted the Declaration of the Lillooet Tribe. This legal document is key in stating the St’át’imc’s political position in response to the theft of their lands. In this document, the St’át’imc assert that they are the rightful owners of their traditional territories. They also protest the dispossession of their lands by the BC government, the occupation of their lands by white settlers, and the construction of railways on their reserve lands. This document forms the foundation for their political stance and actions since.

In recent years, the St’át’imc have encountered many environmental issues and conflicts on their territories. In 2014, there was a significant tailing pond flood into the Quesnel and Fraser Rivers, which are important sources of salmon (watch the video below to hear more). A second struggle is the Bridge River Hydroelectric Complex. This project consists of three dams and stores water for four generating stations. The consequences of this project have been numerous: flooding; relocation; and the loss of fisheries and hunting, trapping, and gathering sites used by many families. For this reason, many families must now share fishing sites due to the loss of so many.

[ezcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1half]

[ezcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

St’at’imc: The Salmon People

The short 2016 documentary, “St’at’imc: The Salmon People,” looks at St’at’imc relations with the salmon, and how hydroelectric dams and forestry projects on their territories have affected their livelihoods. It looks at how industrial pollution — including the devastating Mount Polley mine disaster of August 2014 — has impacted them, and concludes with a brief treatment of St’at’imc monitoring and conservation initiatives.

[/ezcol_1half_end]

In response to the Bridge River Hydroelectric Complex, the St’át’imc drafted declarations, similar to the 1911 Lillooet Tribe Declaration. The purpose of these declarations was to cooperate with the BC Government in an effort to protect their lands and their waters, the latter of which is their most important resource. Kukwpi7 Qwalqwalten Garry John (Xaxli’p First Nation) remarked at the 2015 CICADA conference that the St’át’imc are involved in these collaborative efforts with the Government of BC because they do not have a treaty. This is because treaties are based on extinguishing rights, and the St’át’imc are not in a position to agree to having their rights extinguished, as they have the responsibility as stewards to look after their lands. Instead of agreeing to a treaty, the St’át’imc have outlined certain codes that BC Hydro must follow in order to continue utilizing St’át’imc lands. In one instance, for example, the St’át’imc prevented logging from occurring around Seton Lake. Finally, in 2011, the St’át’imc signed the The Bridge/Seton River Watershed Plans agreement with BC Hydro. This agreement covers the entirety of St’át’imc territory affected by BC Hydro’s footprint. The St’át’imc have also elaborated a five-point governance strategy. The points are the following: direct action; legal action; negotiation; communication and outreach; and ceremony and prayer.

The St’át’imc are involved in other initiatives to ensure that their lands and their heritage are well protected:

Land Use Plan

In 2004, the St’át’imc drafted their Land Use Plan. This plan establishes protected areas for certain species, such as grizzly bears and mule deer. It also creates cultural protection sites that blanket their territory in a complex way. Finally, it describes the St’át’imc tribal code, which governs all affairs on St’át’imc territory.

Lower Bridge River Spiritual and Cultural Value Monitoring Project

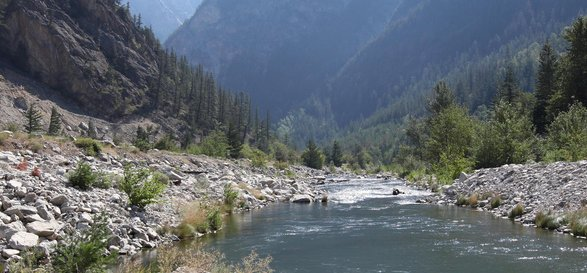

The Lower Bridge River Spiritual and Cultural Value Monitoring Project is part of a project shared between the St’át’imc and BC Hydro on water use planning. These two parties are attempting to coordinate water use in order to ensure water quality and to benefit the riparian habitat, as well as fisheries. The fisheries are especially important, as the spring salmon run was almost depleted due to the hydroelectric project. St’át’imc Elders, who are able to understand the voice and the spirit of the Bridge River, have observed that the water quality has improved noticeably since this project has begun.

Gwenis Forever Project

The purpose of this project is to document past and present knowledge about the deep spawning kokanee salmon (gwenis) in Anderson Lake and Seton Lake. The kokanee salmon in these lakes are a distinct phenomenon. They are land-locked salmon that emerge every winter as a gift from the lake to the shore when the warm Chinook wind blows, to feed people in times of scarcity. This gift is shared with all of the species in the environs, such as bald eagles and wolves. This is a metaphor for the Creator and the land looking after the people. This project is exploring the massive depletion of gwenis and trying to find ways to address the impact. A common St’át’imc saying is, “The fish, the river, the lake are life. When the fish are gone, the people will be gone too.” Those involved in this project are gathering information to educate youth about gwenis and to encourage more harvesting along the lakes.