Eeyouch (James Bay Cree)

Eeyou Istchee (James Bay), Quebec

Hydroelectricity

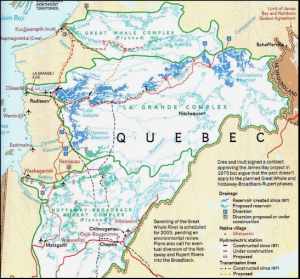

In the late 1980s, Quebec proposed the Great Whale hydroelectric project. The Crees felt that Quebec was not upholding the agreements made in the JBNQA, so in response the Crees protested and successfully managed to shelve the Great Whale project for many years. In 2002, the Crees and Quebec signed the Paix des Braves. With this agreement, the Crees were able to influence Quebec to not follow through with the NBR project to its full extent; the NBR project was replaced with the Eastmain-1-A-Sarcelle-Rupert project, thus ensuring that less land was flooded.

Forestry

Christopher Beck, representative of the Department of the Environment and Remedial Works under the Eeyou Protected Area Committee, works in partnership with CICADA on issues of forestry and protected areas in Eeyou Istchee. On Eeyou Istchee, there has been over 70,000 km2 of forestry development, with more than 2,000,000 m3 of wood harvested per year. In order to permit this high level of forestry, over 15,000 km of roads have been built in the area. Five Cree communities (or 125 traplines) are affected by forestry, while 16,000 non-Crees live in a small number of resource-based towns in this area.

Sociologist Sara Teitelbaum explained at the 2015 CICADA conference that Quebec forestry legislation does not have provisions for consultation with indigenous peoples about forestry activities. Some of the major effects of forestry include pollution from pulp and paper mills; destruction of wildlife habitats; dumpsites from forestry camps; and increased access into Eeyou Istchee from major roads, which increasingly introduces sport hunting, mining, and hydroelectricity to the area. In the 1990s, the Crees felt that forestry was become a threat to their culture and territory.

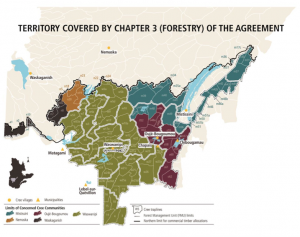

Chapter 3 of the 2002 Paix des Braves agreement created an “Adapted Forestry Regime” with provisions for the improved harmonization of forestry activities with the Cree traditional way of life. The Adapted Forestry Regime provides for special management standards including mosaic cutting and minimum forest cover requirements, and outlines areas of special interest for wildlife, to maintain the habitat of key species such as moose, beaver, fish and caribou.

READ: Paix des Braves – Chapter 3 Adapted Forestry Regime (Cree Quebec Forestry Board)

Protected Areas

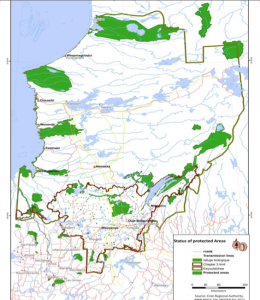

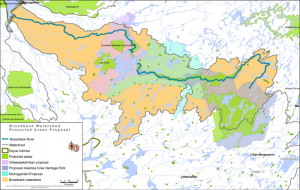

Designation of lands that are protected from industrial development has been increasing in Eeyou Istchee since 2003. Some of the areas were developed and proposed by Cree communities, while others were established by the Quebec Government without adequate consultation and input from the Crees. At the grassroots level, the Cree Nation has developed the Cree Regional Conservation Strategy. The main goal of the strategy is to create an interconnected network of conservation areas in Eeeyou Istchee, in order to safeguard the Cree way of life and sustain biodiversity. Further, the aim is to ensure full Cree participation in conservation areas planning and management. Wildlife conservation and food security are key elements of the strategy, and the best of Cree knowledge and conservation science is being used in this process.

The Marine Region Protected Areas are a group of Cree-established marine conservation sites. As explained Colin Scott at the 2015 CICADA conference, it is an artificial construct to separate marine and terrestrial territories in the creation of protected sites, yet this is the political reality. The Tawich Marine conservation Area was developed in Wemindji and proposed to the Federal Government in 2009. Shortly thereafter, the Crees voted in favour of the Eeyou Marine Region Lands Claims Agreement. Implementation of this agreement involves land use planning and the creation of protected areas. Implementation structures and staffing are currently being put in place to ensure that coastal communities are properly consulted.

Chantal Otter-Tetreault, Environment Analyst with the Grand Council of the Crees and CICADA indigenous partner, mentioned that one site that many northern communities are very keen to protect is Lake Bienville. This is an area that is slated to become a hydroelectric reservoir. The Crees are actively engaged in difficult negotiations with Quebec to protect this important marine site, as well as other marine sites that are part of the Broadback Watershed Conservation Plan. Besides identifying and establishing terrestrial and marine protected areas, the Crees have been very strategic in accepting and rejecting mining projects on their territory. In recent years, they have accepted a gold mine near Wemindji and a diamond mine near Mistissini; however, they have placed a moratorium on uranium mining in Eeyou Istchee.

READ: Forestry and Protected Areas in Eeyou Itschee (INSTEAD presentation, 2014) – Christopher Beck

Cultural Projects

Sammy Blackned of the Cree Nation of Wemindji has been in partnership with PhD candidate and Heritage Research Coordinator Katherine Scott to assist in Wemindji’s realization of a Wemindji Cultural Museum. Katherine has helped in the documentation of cultural practices and, together with the community, she has assembled a book detailing the community’s process of making Shaashtichishaan, a Cree delicacy. Sammy, Katherine, and PhD candidate Geneviève Reid are also assisting in the community’s project of documenting traplines for the Museum, as well as traditional clothing, crafts, and cooking practices.

Mapping

John Bishop has been working with the Cree Nation of Wemindji at the Cree Nation Government Place Names Program, which began in 2013 with the purpose of establishing a Cree language commission and safeguarding the Cree language. The project focuses more specifically on the traditional names of geographical entities, such as communities, trap lines, or lakes. As Bishop states, the project is mainly a proactive effort given the high rates of Cree fluency in Wemindji. The project is concretized through a geographic database of maps which indicate not only traditional place names, but also bits of information that help explain the linguistic and cultural history of those names. As such, the database deals with more than just one type of information, but also any type of multimedia which can add a layer of understanding to the name. The project is also a response to the inadequate maps of the region provided by the Canadian government, which may not only present names in incorrect Cree spelling, but also change traditional Cree names to English or French ones. At CICADA’s 2016 Meeting, Bishop stressed:

As such, the goal of the Place Names Program is to produce maps specifically geared for the use of Cree individuals and for the maintenance of their language. Part of the reason why maps are being increasingly used in Cree communities is due to the gradual loss of traditional knowledge. Sammy Blackned of the Cree Nation of Wemindji mentions at CICADA’s 2016 Meeting:

Therein lies the importance of the Place Names Program, whereby the knowledge originally transmitted through a traditional lifestyle is now being passed on and preserved thanks to new tools and technologies.

Research

Colin Scott, Director of CICADA and INSTEAD, has worked extensively with the Eeyouch. He has studied indigenous and non-indigenous co-management in development projects and has focused specifically on this topic in relation to “The New Relationship Agreement” between the Eeyouch and the Government of Quebec.

“In what circumstances and by what means do resource “co-management” regimes, beyond casting Aboriginal representatives in a merely advisory or consultative role vis-à-vis the state, facilitate real power sharing?”

-Co-Management and the Politics of Aboriginal Consent to Resource Development: The Agreement Concerning a New Relationship between Le Gouvernement du Québec and the Crees of Québec (2002)

Monica Mulrennan, a CICADA academic partner, has also done work with the Eeyouch. Her work has looked at the ways in which the Eeyouch have modified their landscape in order to maintain and enhance desirable conditions for hunting in the face of environmental change.

“While landscape modifications are motivated by a desire to increase resource productivity and predictability, they also reflect an intergenerational commitment to the maintenance of established hunting places as important connections with the past.”

–Securing a Future: Cree Hunters’ Resistance and Flexibility to Environmental Changes, Wemindji, James Bay

CICADA partners Nicole Fenton, along with Hugo Asselin and MA student Mhaly Bois-Charlebois, has done research on the appropriate compensation for resource extraction, specifically gold mining, in Eeyou Istchee. In her research, she has engaged with Eeyou community members in order to gain an understanding of the Cree perspective on ecosystem services.

Associated Projects

Environmental Impact Assessment and Social Impact of Mining in Eeyou Istchee, Nunavik, and Nunavut

Protected Areas Development and Environmental Stewardship, Eeyou Istchee (Crees of northern Quebec)