Atikamekw

Nitaskinan (St. Maurice Valley), Quebec

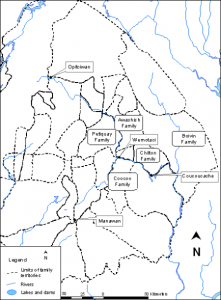

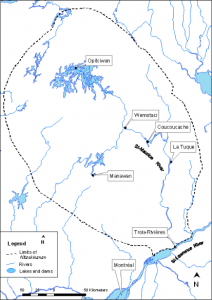

The Atikamekw are a Nation composed of approximately 7,000 people, living primarily in three reserves, namely Wemotaci, Manawan, and Opitciwan. Their ancestral territory, Nitaskinan, is located among the boreal forests and watersheds of the St. Maurice River in northcentral Quebec. The Atikamekw were a hunter-gatherer people and they still regularly practice hunting, gathering, and fishing, even though they have been largely dispossessed from their territory and marginalized by the Canadian State. The Atikamekw have also continued to exercise their customary tenure system, which is based on extended family territories. This has come under threat by administrative delimitations and resource management legislation in Quebec, however, and the province continues to practice logging, lease land for resorts, and control harvesting zones in Nitaskinan.

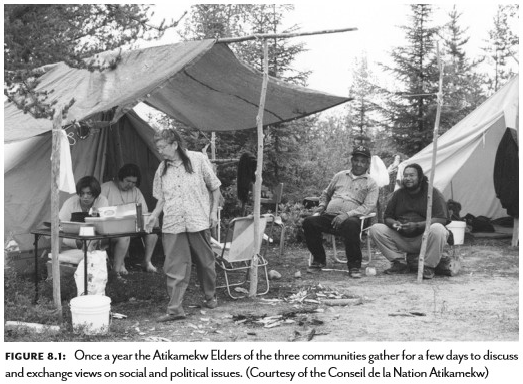

In order to protect their culture, language, and identity, Gerald Ottawa of the Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw explained at the 2015 CICADA conference that the Atikamekw must also protect their territory. The Atikamekw are currently engaged in struggles at three different levels to gain autonomy and sovereignty. First, they are involved in land claims negotiations with the federal and provincial governments to have their traditional territory recognized. Second, at the regional level, they are attempting to convince municipal governments to reduce leasing their claimed territory to non-indigenous peoples for the use of resorts. And third, in their own communities, the Atikamekw are involved in the social and cultural project of transmitting Atikamekw values and knowledge to the younger generations. They are also working to adapt their customary tenure system to current constraints.

“Witamowikok aka wiskat e ki otci pakitina-mokw kitaskino, nama wiskat ki otci atawanano, nama wiskat ki otci mecko-tonenano, name kaie wiskat ki otci pitoc irakonenano kitaskino. (Tell them we have never given up our territory, tell them we have never sold or traded it, tell them that we have never reached any other sort of agreement concerning our territory.)”

-César Néwashish, a most respected Elder who died in 1994 (age 91). (Source: “The Atikamekw: Reflections on their Changing World” in Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, 2013).

Anthropologist and academic partner Sylvie Poirier works with the Atikamekw, exploring notions of territoriality and knowledge. Poirier seeks to understand how these concepts impact the land claims process in which the Atikamekw are currently engaged with the federal government in order to have rights on their own territory. In particular, Poirier has studied the Atikamekw Kinokewin project, whose aim is to facilitate the intergenerational transmission of Atikamekw knowledge. Christian Coocoo of the Conseil de la Nation Atikamekw identified three challenges to the transmission of knowledge: 1) the creation of reserves; 2) residential schools; and 3) young people’s penchant for social media.

“The Atikamekw family territories as postcolonial spaces have thus become the grounds of complex coexistence, negotiations, and entanglement between indigenous and non-indigenous regimes of values, land tenure systems, forms of governance, and conceptions of the forest lands and its nonhuman inhabitants.”

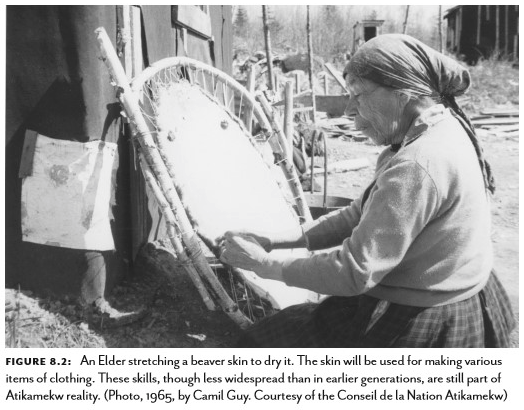

These challenges to knowledge transmission are ones that the Atikamekw are attempting to overcome. Despite all of their struggles with the State, the Atikamekw have continued to practice their traditional activities. Indeed, they engage in 233 traditional activities on their territory during all six of the Atikamekw seasons. The aim of traditional activities is for families to gain and maintain self-sufficiency, while also ensuring the continuity of the flora and fauna on their territory. In order to protect their resources, the Atikamekw have territorial chiefs who know the ins and outs of their territory, including all of the resources, and who decide how the resources are to be used. As explained Gerald Ottawa at the 2015 conference: “Qu’est-ce que la base territoriale? C’est la connaissance écologique traditionnelle de nos aînés atikamekws. C’est à partir de cet élément de base que le travail d’élaboration du code de pratique, la planification sur l’occupation et contrôle territorial, la planification sur le prélévement des ressources naturelles, la protection territoriale et l’aménagement forestier devra être développé.” (“What is territory? It is the traditional ecological knowledge of our Atikamekw elders. It is from this foundation that the development of a code of practice, the planning of occupation and territorial control, the planning of the use of natural resources, territorial protection and forest management should be developed.”)